VIEWPOINT

Canadian pathologists in crisis: a review of national well-being and workload data

![]()

Raymond Maung, MBBS, Michael Bonert, MD,

Britney Soll, BSc(Hon), Heather Dow, CAE, CPC(HC)

Background: Canadian pathologists lack workload protection, resulting in excessive unpaid overtime, which contributes to medical errors, rising medicolegal risk, and mental health deterioration. This crisis has resulted in repeated public inquiries about quality of patient care.

Background: Canadian pathologists lack workload protection, resulting in excessive unpaid overtime, which contributes to medical errors, rising medicolegal risk, and mental health deterioration. This crisis has resulted in repeated public inquiries about quality of patient care.

KEY WORDS: pathology, workload, burnout, workforce, well-being, psychological security

Maung R, Bonert M, Soll B, Dow H. Canadian pathologists in crisis: a review of national well-being and workload data. Can J Physician Leadersh 2025;11(3): 120-130. https://doi.org/10.37964/cr24795

Method: This study is a general review of national data with an observational component. First, we correlated workforce-to-population ratio with medicolegal burden. Second, we used Canadian Medical Association (CMA) wellness survey data to rank pathology against other specialties in terms of 17 wellness indicators.

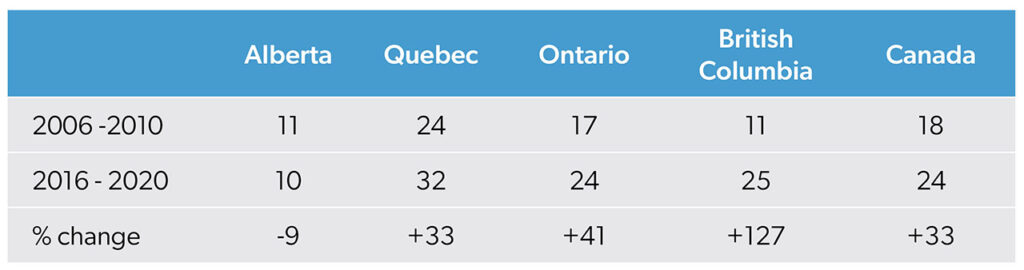

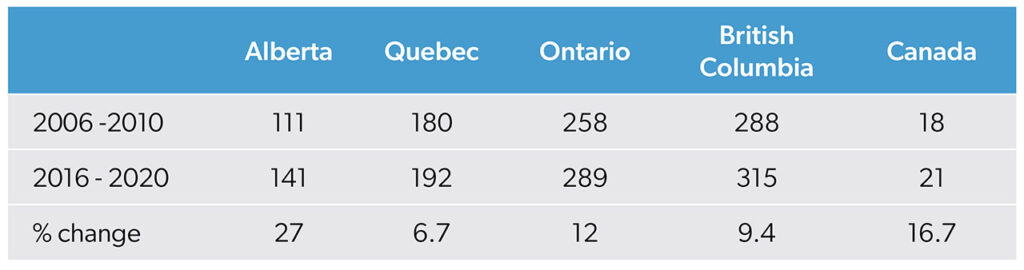

Results: From 2006–2010 to 2016–2020, medicolegal cases per pathologist rose disproportionately. This was most evident in British Columbia (127% increase in complaints vs. 9.4% growth in workforce) and Ontario (39% vs. 15%). Nationally, complaints rose 33% vs. a 16.7% workforce increase. In contrast, Alberta, with the highest workforce growth (27%), saw a 9% decline in complaints. Pathologists ranked worst on 14 of 17 wellness indicators in the 2018 CMA wellness survey. They reported the lowest levels of psychological well-being and the highest rates of distress. Pathologists had a 2.44-fold increased risk of low psychological well-being compared with physicians in other specialties.

Interpretation: The pathology workforce crisis is driven by excessive workload, inadequate structural support, and rising medicolegal scrutiny, which collectively erode well-being. Addressing these issues requires systemic reform, workload-based contracts, and mental health protections to sustain both physician wellness and patient care quality.

Pathologists strive to deliver the highest quality of patient care. The precision and quality of that care are improving — medicine’s evolving knowledge base has enabled meticulous management of complex cases, ancillary studies have expanded, and reporting requirements have become more rigorous.1,2 Despite their increased workload, pathologists do the best that they can — until they no longer can. Currently, Canadian pathologists face an employment model that is unique in Canadian medicine; it lacks workload protections and forces them into excessive unpaid overtime without contractual safeguards. This contributes to rising medicolegal risk and deteriorating mental health.

Laboratories face unpredictable specimen volumes, making workload management difficult. A study analyzing pathology reports from 2011 to 2019 found that, despite a 6% decrease in total cases per year, the workload of pathologists increased substantially: 20% more “blocks,” 23% more workload units, and 19% more report lines.1 This was matched by only a 1% increase in the workforce.1 Unlike that of fee-for-service physicians, pathologists’ workload is not tied to compensation. Hospitals have little incentive to pay for overtime, leading to prioritization of increased output from existing staff rather than hiring additional pathologists.3

Unionization is illegal in most provinces, and Ontario’s Employment Standards Act4 excludes physicians, leaving salaried and contracted pathologists without labour protections. As a result, pathologists must manage overwhelming workloads without mechanisms to redistribute cases or advocate improved conditions. These demands, coupled with systemic neglect, contribute to severe professional distress.

Unsurprisingly, Canadian pathologists experience some of the worst mental health outcomes in the Canadian medical profession.5 A pre-pandemic study found burnout rates among Canadian pathologists of 57.7%6 — exceeding the 35–40% reported among American pathologists who operate under a fee-for-service model.7 Lack of workload control is a primary driver of burnout and disengagement among pathologists8 and is associated with increased medical errors and higher medicolegal exposure.9 Excessive workloads and task maldistribution also contribute to staff absences and departures, further straining the remaining workforce1,8 and damaging morale.

This study presents a national-level review of workforce data. Its primary objective is to examine the relation between the Canadian pathologist workforce and medicolegal risk over time. A secondary objective is to compare the well-being indicators of pathologists with those of other medical specialties.

Method

Design

We carried out a general review using an observational approach. Because of the lack of a unified national dataset linking workforce data with medicolegal cases, we aggregated independent datasets. To our knowledge, these are the only national datasets covering the pathology workforce, medicolegal trends, and physician wellness in Canada.

We conducted two independent analyses: the relation between workforce and medicolegal complaints; and the well-being of pathologists compared with other specialties.

Data sources

To study the relation between workforce and medicolegal complaints, we looked at data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information.10 Workforce data included the number of pathologists per 100 000 population, specialty, and province. For statistical reasons, only large provinces (British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and Canada as a whole) were included. Specialties included in the analysis were anatomical pathology, general pathology, hematological pathology, and neuropathology.

On our request, the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) provided data on self-reported medicolegal cases of its members by province and specialty. The 2006–2010 and 2016–2020 periods provided by the CMPA dictated the periods included in the analysis. Data included civil complaints, college complaints, and hospital complaints.

For the second study, pathologists’ well-being, we examined the CMA National Physician Health Survey (2018),5 which included mental health data, such as burnout and workplace stressors, with laboratory specialty-specific findings. The 2021 survey11 did not separately identify lab specialists, making the 2018 survey the most recent dataset.

Analysis

An observational analysis explored the relation between the number of practising pathologists per 100 000 population and medicolegal complaints per 1000 members of the CMPA, by region. Because of the limited number of cases, data were aggregated into two five-year periods. Aggregation was performed by averaging workforce numbers and medicolegal cases within each period. These values were not normalized further. Given that both datasets were independent and confounders could not be controlled, the analysis remained descriptive and exploratory. The relation between workforce changes and medicolegal case volumes was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

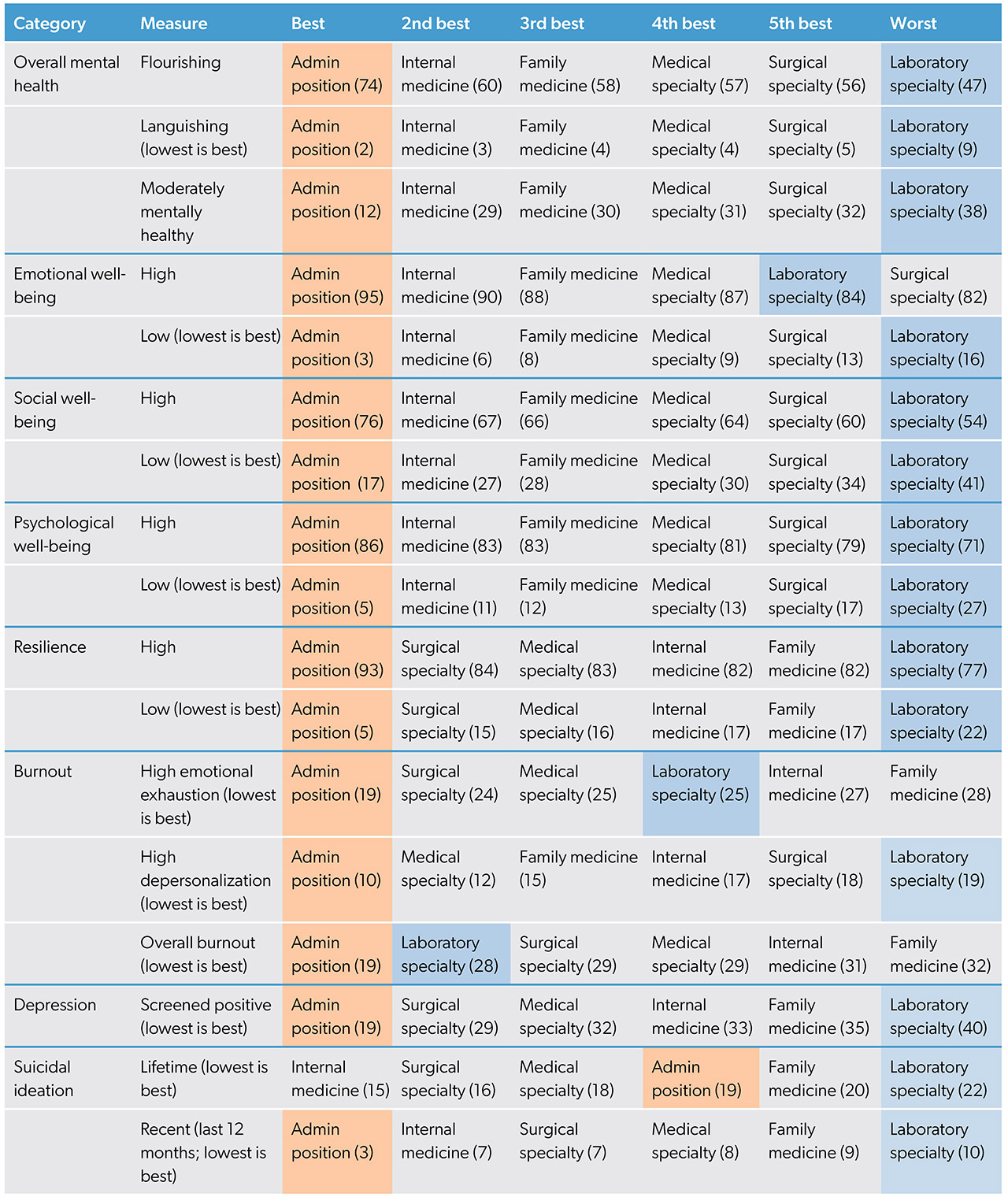

Mental health rankings by specialty were determined using 17 wellness indicators from the CMA 2018 National Physician Health Survey.5 Each specialty was ranked best to worst based on flourishing mental health, emotional well-being, burnout, and depression screening positivity. Positive indicators (e.g., psychological well-being) were ranked in descending order, while negative indicators (e.g., burnout, suicidal ideation) were ranked in ascending order. Because of the lack of access to raw data, sensitivity analyses were not possible.

Ethics approval

As all data were either publicly available (CIHI, CMA) or available on request from the controlling organizations (CMPA), this study did not require ethics approval under institutional and national research ethics guidelines.9

Results

During the study period, medicolegal complaints rose by 33% (Table 1), far outpacing workforce growth (Table 2), suggesting an escalation of the burden per pathologist. A Spearman’s rank correlation (rS(3) = −0.56, p = 0.322) indicated a moderate negative correlation, suggesting that as workforce grew, medicolegal cases increased disproportionately per pathologist. This trend was most pronounced in British Columbia (127% increase in complaints compared with a 9.4% increase in workforce) and Ontario (41% increase in complaints compared with a 12% increase in workforce). This trend was opposite in Alberta, where a 27% increase in workforce was accompanied by a 9% decrease in complaints.

Note: Medicolegal cases are self-reported to the CMPA at the plainant’s discretion; therefore, data may not include all cases. Data are also based on case closure; other cases involving pathologists may still have been open at the time of data extraction.

In terms of well-being, pathologists ranked worst in 14 out of 17 mental health indicators in the CMA 2018 National Physician Health Survey (Table 3). Administrative positions rank highest in all but one factor, while pathology (laboratory specialty) ranked worst in most categories. Pathologists reported the lowest ratings of high psychological well-being (71%) and the highest rate of low psychological well-being (27%) — a 2.44-fold increased risk (144%) compared with other physicians (see 2018 National Physician Health Survey,5 page 13, ɑ = 0.004, adjusted for multiple comparisons). This disparity is larger than the gap in psychological well-being between any two other specialties.

Source: Canadian Medical Association 2018 National Physician Health Survey.5

Pathologists also reported the lowest overall flourishing mental health rate (47%) and highest languishing rate (9%). They scored second lowest in emotional well-being (84%), lowest in high social well-being (54%), and highest in low social well-being (41%). Depression rates were highest (40%), and burnout was significant and comparable to other specialties, with 25% of pathologists experiencing emotional exhaustion and 19% reporting depersonalization. Suicidal ideation rates were elevated, with 22% lifetime prevalence and 10% of pathologists reporting recent suicidal thoughts, similar to rates observed in family medicine and medical specialties.

Interpretation

Our analysis found that medicolegal complaints against pathologists increased in all provinces but Alberta, suggesting an increase in errors that impact patient care. Pathologists ranked last in wellness indicators, with higher rates of burnout, depression, and suicidal ideation than most other specialties. Comparatively, administrators, who have the greatest control over workload, ranked highest in well-being indicators. This supports the importance of control over one’s work environment.

Between 2006–2010 and 2016–2020, we found a marked increase in medicolegal cases per pathologist. This trend may reflect increasing workload pressures, case complexity, and evolving medicolegal scrutiny. Excessive workload is associated with increased medicolegal risk and errors.12 Patient safety is affected when pathologists work more than 39 hours per week;13 Canadian pathologists work an average of 59 hours per week, including 19 hours of unpaid overtime.13 The consequences of chronic burnout extend to increased medical errors and decreased diagnostic accuracy, posing a direct risk to patient outcomes.14 In contrast to other provinces, Alberta, which has adopted the Canadian Association of Pathologists’ level 4 equivalent system,15-17 had the greatest growth in workforce (27%) and was the only province to see a decrease in medicolegal complaints (-9%).

International data suggest that pathology workload has intensified through increased case complexity and expanded reporting requirements.1,2,18,19 In addition, task maldistribution contributes to staff departures, which place further strain on an already understaffed system8 that falls under public scrutiny for high-profile diagnostic errors.20,21 In 2025, there were 118 unfilled pathology resident positions.22 These findings suggest that the increasing medicolegal burden faced by pathologists may be driven in part by systemic workload pressures, which continue to rise without corresponding workforce expansion or structural support.

Pathologists face a 2.44-fold risk of low psychological well-being compared with other physicians,5 which aligns with recent findings that burnout, depression, and anxiety are prevalent in the profession.5-8 The solitary nature of pathology — with minimal social engagement and collegial interaction — further exacerbates these challenges.6 Chronic work-related pain, particularly musculoskeletal strain from prolonged sedentary work and repetitive tasks, has been identified as a significant but underrecognized contributor to burnout.6,23 However, limited work flexibility is the strongest predictor of burnout among Canadian pathologists.6

Beyond workload, lack of psychological safety in workplace culture, exacerbated by the established “culture of bullying” in the Canadian medical fraternity,24-26 may contribute to poor well-being. A 2018 study found that up to 75% of Canadian resident physicians had reported harassment and/or intimidation.26 Similar rates were observed in an American study, which established that the intensity of workplace incivility increased the number of sick days taken by laboratory practitioners.27 In response to a webinar on burnout in Canadian pathologists, participants raised concerns that mental health is often dismissed by hospital administrators as “whining.”28 Combined, these circumstances appear to reinforce a culture of silence in the profession and create barriers to developing psychological safety.29

Limitations and knowledge gaps

As a general review with an observational component, this article synthesizes national datasets that were not designed for direct comparison, limiting the ability to adjust for confounders, such as regulatory changes, differences in case adjudication, or provincial variation in medicolegal reporting. Furthermore, as Canadians physicians report their medicolegal cases to the CMPA at their own discretion, the data may not include all cases. In addition, the analysis does not consider such factors as policy shifts and increased legal scrutiny.

The analysis of mental health ranking lacks weighting, meaning that indicators with high prevalence (e.g., burnout) may have a disproportionate influence on specialty rankings. Because of data restrictions, a sensitivity analysis was not conducted, preventing further validation. Mental health data specific to pathologists are limited; the 2018 CMA survey5 remains the only national dataset that disaggregates laboratory specialists, leaving post-pandemic trends unexplored. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Call to action

In light of the evidence, we urge provincial health leaders and pathology departments to champion change collaboratively. We recommend:

- Shifting from time-based to workload-based contracts to ensure equitable compensation for consultative, administrative, and academic duties, using Laboratory Information Systems (LIS) data to track workload.

- Including pathologists as key stakeholders in defining workload benchmarks. A national workload model should standardize benchmarks and support fair distribution.

- Transparent workload tracking to improve accountability, morale, and staffing decisions. Transparency would improve morale by addressing actual or perceived workload imbalances and facilitating cooperative crisis management.

- Collaboration between leadership and pathologists to oversee the implementation of well-being initiatives and policies aimed at reducing workplace bullying, with the aim of fostering a transparent and equitable environment and a culture of psychological safety.

Conclusion

Canadian pathologists face a high level of medicolegal risk and mental health disparities relative to other specialties. The disproportionate increase in medicolegal complaints relative to workforce growth may reflect rising error rates, regulatory scrutiny, or evolving medicolegal frameworks. Pathologists consistently rank worst in well-being indicators and are at high risk of poor psychological well-being.

This national review makes clear that Canadian pathology is at a tipping point — burnout and workload pressures are not only undermining pathologists’ well-being but may also threaten the quality of patient care. Implementing nationwide workload standards and pathologist wellness programs and addressing workplace culture could serve as critical interventions. Without systemic changes, the profession risks further attrition and widening gaps in patient safety. A coordinated, evidence-based response is urgently needed to sustain the pathology workforce and safeguard the integrity of Canada’s health care system.

References

- Bonert M, Zafar U, Maung R, El-Shinnawy I, Kak I, Cutz JC, et al. Evolution of anatomic pathology workload from 2011 to 2019 assessed in a regional hospital laboratory via 574 093 pathology reports. PloS One 2021;16(6):e0253876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253876

- Maung RT, Geldenhuys L, Rees H, Issa Chergui B, Ross C, Erivwo PO. Pathology workload and human resources in Canada — trends in the past 40 years and comparison to other medical disciplines. Can J Pathol 2020;12(1):16-29.

- Bonert M, Zafar U, Maung R, El-Shinnawy I, Naqvi A, Finley C, et al. Pathologist workload, work distribution and significant absences or departures at a regional hospital laboratory. PloS One 2022;17(3):e0265905. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265905

- Employment Standards Act, 2000, S.O. 2000, c. 41. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2024. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/00e41

- CMA national physician health survey: a national snapshot. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 2018. Available: https://digitallibrary.cma.ca/link/digitallibrary18

- Keith J. The Burnout in Canadian Pathology Initiative. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2022;147(5):568-76. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2021-0200-OA

- Garcia E, Kundu I, Kelly M, Soles R, Mulder L, Talmon GA. The American Society for Clinical Pathology’s job satisfaction, well-being, and burnout survey of laboratory professionals. Am J Clin Pathol 2020;153(4):470-86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa008

- Smith SM, Liauw D, Dupee D, Barbieri AL, Olson K, Parkash V. Burnout and disengagement in pathology: a prepandemic survey of pathologists and laboratory professionals. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2023;147(7):808-16. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2022-0073-OA

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans. Ottawa: Interagency Secretariat on Research Ethics; 2014. Available: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.700182/publication.html

- Physicians per 100 000 population, by specialty. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health information; 2024. Available: https://tinyurl.com/36s674ye

- CMA 2021 national physician health survey. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 2022. Available: https://digitallibrary.cma.ca/link/digitallibrary17

- Li CJ, Shah YB, Harness ED, Goldberg ZN, Nash DB. Physician burnout and medical errors: exploring the relationship, cost, and solutions. Am J Med Qual 2023;38(4):196-202. https://doi.org/10.1097/JMQ.0000000000000131

- Maung R. Work pattern of Canadian pathologists. Diagn Histopathol 2016;22(8):288-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpdhp.2016.07.003

- Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, Zhou A, Panagopoulou, Chew-Graham C et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018l178(10):1317-30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713

- Wright JR, Chan S, Morgen EK, Maung RTA, Canadian Association of Pathologists’ Pan-Canadian Pediatric-Perinatal Pathology Workload Committee. Workload measurement in subspecialty placental pathologist in Canada. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2022;25(6):604-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/10935266221118150

- The Canadian Association of Pathologists workload model. Kingston, Ont.: Canadian Association of Pathologists; 2018. https://tinyurl.com/429p4mth

- Park PC, Kurek KC, DeCoteau J, Howlett CJ, Hawkins C, Izevbaye I, et al. CAP-ACP Workload model for advanced diagnostics in precision medicine. Am J Clin Pathol 2022;158(1):105-11. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqac012

- Khatab Z, Hanna K, Rofaeil A, Wang C, Maung R, Yousef GM. Pathologist workload, burnout, and wellness: connecting the dots. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2024;61(4):254-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2023.2285284

- Stagner AM, Tahan SR, Nazarian RM. Changing trends in dermatopathology case complexity: a 9-year academic center experience. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2021;145(9):1144-7. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2020-0458-OA

- Roberts D. Possible errors in mammography results prompt review at N.L. health authorities. Ottawa: CBC; 2022. Available: https://tinyurl.com/493m7k4s

- Dino A. Damages reduced in breast cancer misdiagnosis case: BC Court of Appeal. Can Lawyer 2024. Available: https://tinyurl.com/33hz2n4c

- Unfilled positions after the second iteration of the 2025 R-1 main residency match — by discipline. Ottawa: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2025. Available: https://tinyurl.com/bdhf9ycw

- Khan S. The dark side of being a pathologist: unravelling the health hazards. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2024;67(1):46-50. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_1148_21

- Vogel L. Culture of bullying in medicine starts at the top. CMAJ 2018;190(49):E1459-60. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5690

- Vogel L. Doctors dissect medicine’s bullying problem. CMAJ 2017;189(36):E1161-2. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1095484

- Vogel L. Canadian medical residents report pervasive harassment, crushing workloads. CMAJ 2018;19:190(46):E1371. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5678

- Chiou PZ, Mulder L, Jia Y. Workplace bullying in pathology laboratory medicine. Am J Pathol 2023;159(4):358-66. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqac160

- Soll A, Dow H. Creating meaning through small doses of actionable learning: a mixed methods analysis of CAP-ACP’s virtual CME activities. Can J Med Specialties 2025;1(2):16-25. https://doi.org/10.63838/001c.142943

- Siad FM, Rabi DM. Harassment in the field of medicine: cultural barriers to psychological safety. CJC Open 2021;3(12 suppl):S174-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2021.08.018

Authors

Raymond Maung, MBBS, MBA, FRCPC, is staff anatomical pathologist at the University Hospital of Northern British Columbia, clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia, and chair of the workload and human resources committee, Canadian Association of Pathologists.

Michael Bonert, MASc, MD, FRCPC, is a staff anatomical pathologist at St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, and an assistant professor at McMaster University.

Britney Soll, BSc(HONS) psychology, is a DCPsych candidate at the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling and candidate, Middlesex University.

Heather Dow, CPhT, CAE, CPC(HC), HPDE, HMCC, is the executive director of the Canadian Association of Pathologists.

Attestation: RM was the principal investigator and was responsible for sourcing data. RM and MB conducted the initial analyses and drafted the manuscript. RM, MB, BS, and HD were involved in the analysis, writing, and review of the article. All authors take responsibility for the work.

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests in regard to this study. Details of this project have not been presented or published in any form previously.

Funding: No funding was received for this project.

Data availability: The datasets generated for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Correspondence to:

r_maung@yahoo.ca

This article has been peer reviewed.